Survivors, liberators, diplomats and March of the Living alum gather for remembrance event.

Neshama Carlebach and Eli Rubenstein remember exactly where they were standing in 1998 when Judy Weissenberg Cohen uttered a moving address to a large group of teenagers from Canada attending the 11th March of the Living in Poland. A line in Weissenberg Cohen’s speech describing her Nazi experience in Hungary, which poignantly became known as “The Last Time I Saw My Mother,” painfully notes, “I never had a chance to say goodbye to my mother. We didn’t know we had to say goodbye. And I am an old woman today and I have never made peace with the fact I never had that last hug and kiss. They say when you listen to a witness, you become a witness.”

Carlebach and Rubenstein have both become witnesses. Singer Carlebach, about to attend and sing at her second March of the Living, recalls her first visit to Poland and the march from Auschwitz to Birkenau in memory of Nazi victims.

“I was decimated…I was so completely destroyed by what I was seeing…” In the Rama Synagogue in Krakow, Carlebach “finally understood” and spontaneously stood up to sing the well-known Krakow Niggun, composed by her late father, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. The niggun (wordless melody), which moves from slow and mournful to upbeat and celebratory, was inspired by a dream Carlebach had on a visit to Auschwitz. He was reportedly so sad that he fell asleep and had a dream in which naked Jewish prisoners were going to their deaths—and were suddenly transformed into people wearing white clothes, with big smiles on their faces. “Until then, I didn’t take my work as a healer seriously. You become a witness. I was there. I feel it even now speaking to you!”

Rubenstein, National Director of March of the Living Canada, is also co-curator of the March of the Living exhibit which premiered at the United Nations in New York City on January 28 —one day after International Holocaust Remembrance Day, an annual day of commemoration established by the United Nations.

The title of the exhibit, “When you Listen to a Witness, You Become a Witness,” comes from Weissenberg Cohen’s poem of 1998.

Sara Jaskiel, a Brooklyn-based graphic artist and designer, found the work of assembling and curating the exhibit “moving, overwhelming and meaningful.”

She recounts, “You think of each person and what happened, and you want to raise sensitivities.”

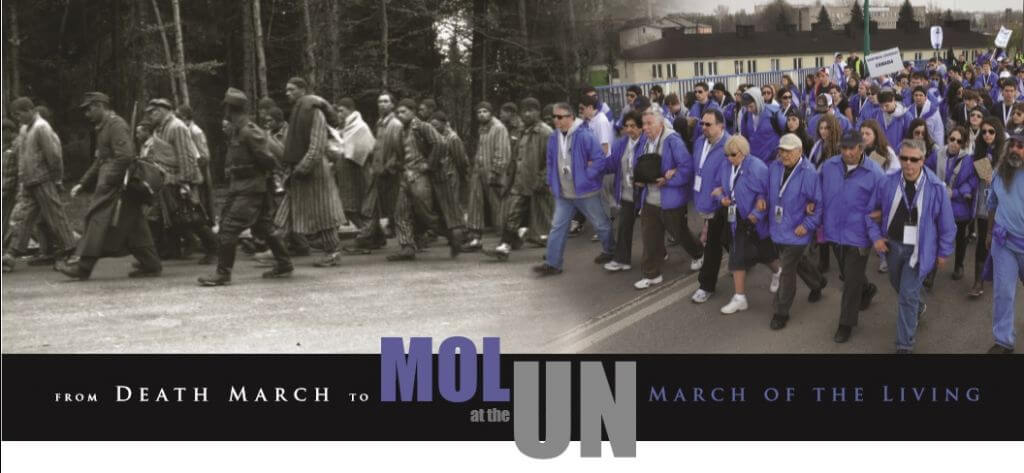

Jaskiel is particularly pleased with the “Death March” photograph she was able to assemble, which served as the backdrop for the musical performances and speeches at the January 28 ceremony.

“I did research and found photographs—from the Death March and from a March of the Living—taken at the same angle. It is as if they are parallel—in a row.. I was able to synthesize the photos.”

The moving photo, which all attendees received in the form of poster, depicts a black and white photo of Jews during the Holocaust and a color photo of Jews on the March of the Living walking “together” from Auschwitz to Birkenau.

Rubenstein, Carlebach, survivors, liberators and dignitaries participated in the January 28 premiere. The evening began with guests viewing the exhibit of photos and poems and socializing over wine and kosher hor d’oeuvres.

What initially seemed like an unusual start to an evening devoted to the Holocaust actually nicely fit with both the theme which each speaker echoed—memory and hope. The formal program began with 2012 March of the Living alumna, Sara Diamond, singing “Eli Eli.”

Peter Launsky-Tieffenthal, the UN’s Under Secretary-General for Communications and Public Information welcomed the guests, noting, “We at the United Nations feel privileged to host this exhibit at UN headquarters as part of our Holocaust Remembrance activities.”

The speakers included Ron Prosor, Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Dr. Shmuel Rosenman, chairman of March of the Living International, Shlomo Grofman, vice chair, Dr. Naomi Azrieli, chair and CEO of the Azrieli Foundation, which publishes survivor memoirs, and Max Glauben, survivor.

The particularly upbeat Glauben, born in Warsaw in 1928, spoke to the Times of Israel before the ceremony, described the exhibit as “a wonderful display” and said he was pleased that it is being housed at the United Nations.

In his public remarks, he recounted his personal story of survival and thanked the liberators in the audience. He also singled out attendee, Israeli Eli Yablonek, and his guide dog, Glen. Yablonek is blind and does not have a left arm. “Eli came on the March of the Living in 2012—with his dog. It shows that the same animals Nazis used to attack people could be used to do good.”

One liberator of Buchenwald, Army Combat Engineer Frederick (Rick) Carrier, dressed in his World War II uniform, recounted in a pre-ceremony interview, “I saw prisoners trying to squeeze through a small gap at the bottom of a fence and I reached for my wire cutters. I cut a big hole in the barbed wire fence.” Carrier, now 90, notes that he didn’t realize the people were Jewish Holocaust survivors.

“We were fighting a war—they never told us anything. We didn’t have any knowledge. They were just awful looking when we discovered them.” Carrier proudly showed off the medals he received when he attended last year’s March of the Living.

Following the address by Prosor, where he commented that “The March of the Living is to remind us as much about life as about loss, and triumph as much as tragedy,” Carrier’s voice could be heard shouting out, “Yeah!”

In an interview with the Times of Israel following the ceremony, Prosor highlighted the significance of the evening’s event.

“This all takes place at the UN—a place where, most days of the year, people don’t unite. But [International Holocaust Remembrance Day on] January 27 brings people from all counties, backgrounds and religions together in understanding.”

Prosor elaborated, “Education about tolerance and acceptance of others is absolutely crucial to creating a different and better society for the future.” When asked who the ambassador would like to bring to see the exhibit, he replied, “school students, the younger generation — so they can be more tolerant.”

Asked which world leaders and countries should attend the exhibit, Prosor noted proudly, “Several ambassadors — perhaps four or five — have come so far. They were touched and will educate others.” He concluded, “It is no coincidence that the Hungarian ambassador attended. He came out publicly to take responsibility for what Hungary did to Jews during the Holocaust.”

On January 23, several days after the Hungarian Jewish community accused the government of Hungary of engaging in Holocaust revisionism, Hungary’s United Nations Ambassador Csaba Korosi, at an event sponsored by the UN Department of Public Information for NGOs, reported, “We owe an apology to the victims because the Hungarian state was guilty for the Holocaust.”

Hungary has come a long way since the day one Hungarian Jew, Judy Weissenberg Cohen, last saw her mother.

(Source: http://www.timesofisrael.com)