After the experience, participants asked a single question: “When can we come back and do this again?”

View the original post on the Jewish News Syndicate

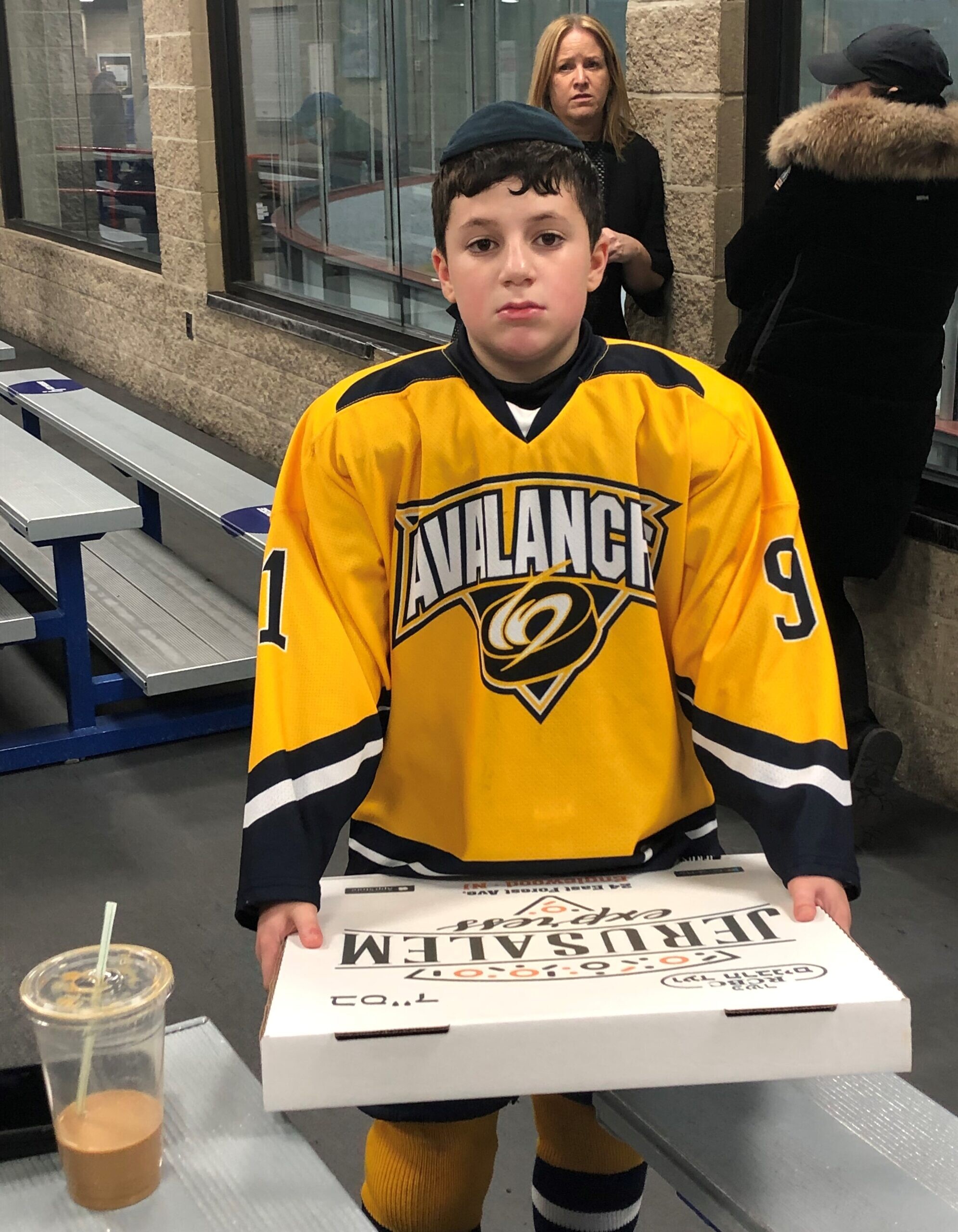

Volunteers on a disability inclusion trip sponsored by Birthright Israel, September 2024. Photo by Howard Blas.

(Oct. 8, 2024 / JNS) Eight days in Israel leading the first-ever Ramah Tikvah Birthright Israel Onward disabilities service trip provided insight into how a group of adults ages 21 to 41—all with intellectual and developmental disabilities (most on the autism spectrum)—are capable of connecting deeply with the Jewish homeland and its people, and of making important contributions through their volunteer efforts.

The delegation, all current participants or alumni of Ramah Tikvah disability inclusion programs, have spent many summers at Ramah camps, where they have forged ties with Israelis from their mishlachot (Israeli delegations), learned Israeli songs and dances, and grown to appreciate the importance of the Jewish state in their lives.

When the war with Hamas in Gaza broke last October following the Hamas terrorist attacks in southern Israel, participants in Ramah Tikvah programs began seeing community and family members—and friends from their respective camp communities—travel to Israel on service trips. They began to wonder if they might have a similar opportunity to contribute during Israel’s time of extreme need.

Perhaps Birthright Israel Onward would offer a solution?

Taglit Birthright Israel offers a dozen “classic” trips with necessary supports and accommodations for participants with mobility challenges, inflammatory bowel disorders and other medical issues, as well as an American Sign Language program, a trip for those in 12-step recovery programs and more. In addition, the Birthright Israel Onward program facilitates internships, fellowships, academic study and volunteer opportunities in Israel.

When I pitched the idea of a volunteer trip for people with disabilities, Onward Israel CEO Ilan Wagner immediately gave the green light. This group would need accommodations not usually provided to typical Birthright Israel Onward participants, including staff accompanying the group on the flight and 24/7 throughout the trip; three meals daily; hotel rather than group apartment accommodations; and additional structured activities once their morning of volunteering was over.

Last month, even as the war in the Gaza Strip and the hostage situation continued and with an escalation of war looming between Hezbollah in the north, 12 participants and four staff members boarded flights or took cars or trains from St. Louis, Detroit, Columbus, Minneapolis, Phoenix, Berkeley, Calgary, New Jersey and New Haven for flights to Israel. We arrived at a hotel in Tel Aviv ate dinner, got some rest and hit the ground running the next day.

We recited the Shehecheyanu prayer in honor of this pioneering trip and had morning services at the Nahum Gutman Mosaic Fountain in Tel Aviv. We then headed out—Bingo cards in hand—in search of various famous Tel Aviv landmarks on the Independence Trail. After lunch, we visited the Israel ParaSport Center in Ramat Gan. Our guide, Caroline, who was born paralyzed, is the No. 6 wheelchair table-tennis player in the world and shared what sports means to her. We also had a chance to watch Israel’s national wheelchair basketball team engage in a tough practice, and after speaking with team members, got to try out the specially designed chairs.

Then, it was off to a small Chabad shul in Tel Aviv to do our part for the Tzitzit for Tzahal project—an initiative to prepare 200,000 pairs of ritual army-green fringes for soldiers.

The next day saw us at Pitchon Lev: Breaking the Cycle of Poverty in Rishon Letzion, where we assembled 180 large boxes and filled each with diapers and four packs of wipes. Following our busy and satisfying morning of volunteering, we had lunch—pizza and grill were both exciting options for the hungry volunteers—before setting off for a special tour of the ANU Museum of the Jewish People on the campus of Tel Aviv University. After dinner, we ended our day with a rhythmic movement activity.

On Friday, we made a trip to Jerusalem so the few first-time visitors to Israel could visit the city. Everyone enjoyed shopping on Ben-Yehuda Street, riding EZRaider electric motorized vehicles, and touring the Old City and the Western Wall before heading back to Tel Aviv in time for prayers, Shabbat dinner and an Oneg Shabbat, complete with an UNO card-game marathon.

Shabbat started with morning prayers at the beach, followed by swimming in the Mediterranean, a walk, lunch and visits by Israeli friends and family members. We ended with a beautiful Havdalah service that reminded participants of the many similar ones at their respective camps.

On Sunday, we set off for the first of two days of olive picking at Harvest Helpers Leket Israel in Rishon Letzion. We learned that our olives would be made into olive oil for Israelis in need. Our participants once again felt a connection between their volunteer work and people receiving direct benefits.

Our afternoon visit to Hostage Square in Tel Aviv was quite emotional. We walked through a makeshift tunnel, looked at the empty Shabbat table and chairs (now under a sukkah) in tribute to the hostages, viewed art installations and purchased “Bring Them Home Now” shirts, dog tags and ribbons.

On Monday, in the middle of our breakfast, the staff learned that out of an abundance of caution as the situation in the north was heating up, we were being instructed by the Situation Monitoring Room to leave the hotel in under an hour and relocate to Jerusalem after our morning of olive-picking. Participants remained calm, adjusting to an abrupt change of plans (not usually easy for people with autism) and quickly packing up. Our scheduled culinary tour in Tel Aviv turned into a similar tour in Jerusalem’s Machane Yehuda open-air market, a walk through the adjoining Nachlaot neighborhood and a stop for some ice-cream.

Our last full day in Israel began at Pantry Packers, where we worked in four-person teams to pack peas and other dried goods for Israel’s needy. After putting on aprons and hairnets, two team members placed separate labels on bags, one operated the machine that dispensed the grains into bags, and one used the sealing machine. Our day—and rewarding week in Israel—began winding down with pizza and a swim party at a brand-new pool at a country club in Har Homa.

Back at the hotel, participants shared highlights of the trip. Annie thanked her “lovely roommate.” She added that “the trip was a good experience for me. I’m going to start crying.” Maddy, who noted that she volunteers thousands of hours per year, felt that the Israel ParaSport visit “got me thinking of physical disabilities in ways I never have.” Jesse felt a true sense of belonging he said he never felt at home. On Birthright, he said, “I feel like you guys were all my family.”

Our tour guide, Rotem, encouraged the group to go home and serve as ambassadors, sharing their experiences. The participants were unified in asking one question: “When can we come back and do this again?”

My hope is that the Jewish community will continue to create meaningful opportunities—in the United States, Canada and Israel—for adults who have both disabilities and amazing strengths, so as to be fully included and feel a sense of belonging.

Howard Blas is a social worker and special-education teacher by training. He teaches Jewish studies and bar/bat mitzvah to students with a range of disabilities, leads disability trips to Israel and writes regularly for many Jewish publications, including JNS.org.