Original Article Published On The Chabad.ORG

KINGSTON, N.Y.—Rabbi Y. Yitzhak Hecht’s sense of humor is as admirable as his sense of determination. When I arrived at Congregation Agudas Achim, he greeted me enthusiastically and playfully with his smartphone in hand, ready to capture my reaction when he introduced me to my namesake, longtime shul member Howard Blas.

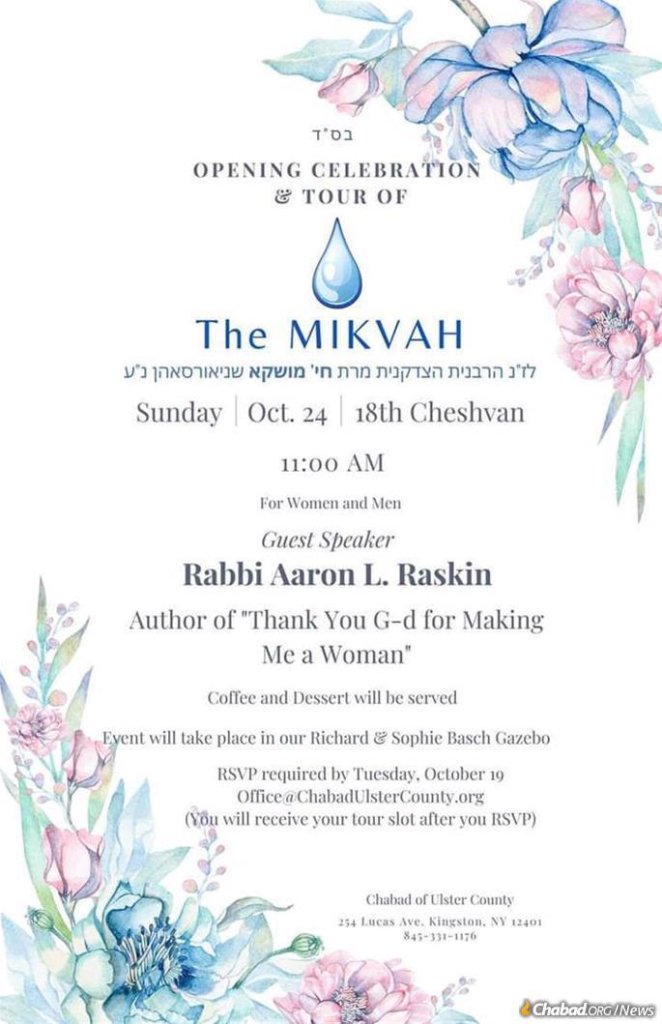

“Howard Blas, meet Howard Blas!” exclaimed the rabbi as we moved along into the congregation’s library and beit midrash, where the he shared news of a state-of-the-art mikvah set to open on Oct. 24, offered updates on daily Torah classes he conducts online with other Hudson Valley rabbis and enthused about the ongoing expansion of Chabad of Ulster County—just 90 miles (145 kilometers) north of New York City and 60 miles (95 kilometers) south of Albany.

When Hecht first walked into the synagogue 20 years ago, just a few days after the terrorist attack on Sept. 11, 2001, the once-thriving 137-year-old Orthodox synagogue had fallen on hard times. The city and its Jewish community had been decimated by the departure of its biggest employer six years earlier. Only two people attended Simchat Torah services the year before, and the shul had six rabbis in seven years, recalls local potter and artist Howard Vichinsky.

But the congregation found the hard-working and good-natured rabbi and his wife, Leah, irresistible, and they have been serving and helping grow the community ever since. Their own family has grown as well with seven of their eight children natives of Kingston.

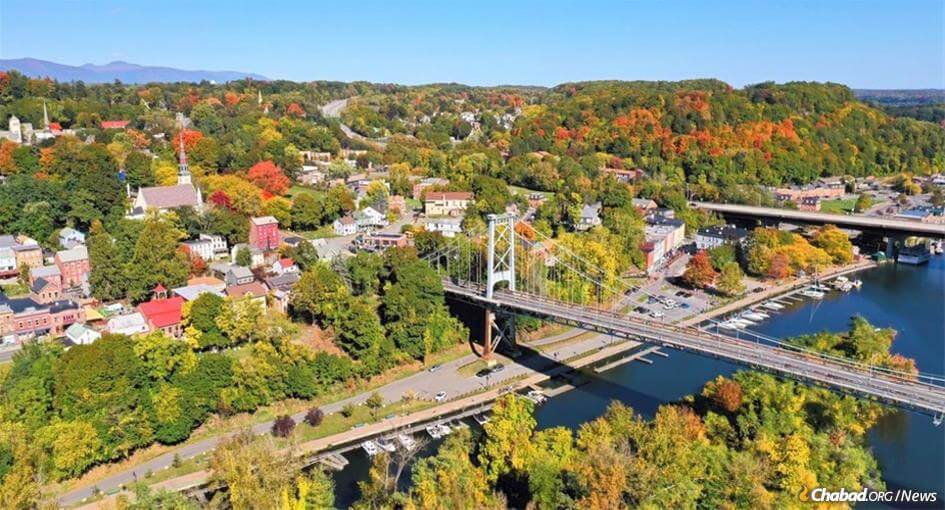

Today, with more people than ever before working remotely, Kingston is becoming a destination for Jewish families in search of open space, good air quality, scenic views, small-town warmth, culture and access to Jewish life. The quaint city on the west bank of the Hudson River has an area of 8.6 square miles and 1.3 square miles, and is about a two-hour commute from New York City.

The Ups and Downs of a Hudson Valley City

Kingston has had many ups and downs in its history, briefly serving as New York State’s capital in 1777 before it was burned to the ground by the British. The city flourished in the 19th century when natural cement was discovered in the area, and with its proximity to the Hudson River and connection to the transcontinental railroad system, it became an important transportation hub.

Jewish families began to settle in the city; in 1864, Congregation Agudas Achim was established by Jewish immigrants from the city of Amdur in Belarus. In the early 20th century, Kingston’s coal and cement industries began to decline. Small machine manufacturing and garment production soon grew, followed by the biggest boom in the city’s history: the arrival of IBM.

In 1954, the computing giant built a 2.5 million-square-foot factory and research center in Kingston and employed more than 7,100 workers at its peak, making up as much as 30 percent of the local economy.

In 1995, IBM abruptly closed its doors and left the city, abandoning the factory. Thousands of people were impacted, and many simply left.

Blas, who has served as shul president four times, worked for IBM for four years. His in-laws have been connected to Kingston and to the Jewish community there for decades. His wife’s grandparents were members, and his daughter is the fifth generation to be davening here, Hecht tells Chabad.org. They have experienced Kingston’s ups and downs firsthand.

Blas recalls the years when the shul dwindled to only 25 members. “Chabad came in 2001. The Sept. 11 terror attacks happened that year, and Rabbi Hecht got here for Rosh Hashanah. The great energy he and his wife had at the start has only increased 10 times since then.”

“He started with a Sunday minyan, which we almost never had,” continues Blas. “Then he began Tuesday minyan with coffee and danishes.”

Blas credits fellow congregant, longtime president and dear friend Howard Vichinsky for getting him more involved in the shul. “I came because of him, and Shabbat was always a big thing for me.”

Today, the congregation has a daily morning minyan, and a full roster of services for locals and guests.

Roots in the Community

The Hechts have roots in the area that date back to the rabbi’s childhood. In 1953, his grandparents, Rabbi J.J. and Rebbetzin Chava Hecht, founded Camp Emunah in Greenfield Park, N.Y. Camp Emunah is the first girl’s overnight camp in the world of Lubavitch. The Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—personally visited the camp. Of the three times the Rebbe travelled outside of New York City after ascending to the leadership of Chabad-Lubavitch, all three were to Camp Gan Israel and Camp Emunah.

Howard and Renee Vichinsky moved from Brooklyn to Kingston in 1983 and have been actively involved since 1984. “I have been president for the last 26 years and gabbai for seven years,” reports Howard proudly. He, too, experienced Kingston’s ups and downs and worked hard to keep the shul going.

He observes, “over time, things change in a rural community. Kids go to college and don’t come back. Jewish farmers no longer farm. Businesses close. By the late 90s, we were in low tide.” He pointed out sadly, “One Simchat Torah, me and another guy—we danced with the Torah.”

Vichinsky also emphasized the toll that IBM’s closing had on the community. “Losing 4,000 jobs in a community of 24,000 was a lot. The community took a big hit.”

‘There are Reasons Why We Don’t Have a Rabbi’

As the community’s numbers dwindled, Vischinsky approached a rosh yeshivah in Monsey, N.Y., who agreed to send rabbinical students every other week to keep the shul alive. This arrangement went on for several years.

“In 2001, Rabbi Hecht knocked on my door and said, ‘I’d like to be the rabbi of the shul.” I explained, ‘There are reasons we don’t have a rabbi.’ Vichinsky was intrigued with Hecht’s unusual offer, acknowledging that “the congregation was a little nervous. They had no familiarity with Chabad. We took a chance, and it has been a wonderful partnership. It was the right combination. It is Chabad’s mission to bring in and bring Jews back to tradition. I have been very happy!”

Vichinsky details some of Hecht’s additional accomplishments, including the Jewish Summer Fellowship. “Ivy League Torah Study—a woman’s summer Torah-study program—needed a home, so we cut the social hall in half and made seven rooms.”

Seven beautifully furnished guest rooms are used regularly by visitors to the community. “There is a very good head trauma center in Kingston, and family members have stayed over several times. Or people who want to spend the High Holidays out in the country stay here.”

Vichinsky, a self-described baal teshuvah, enjoys learning and appreciates the many classes Hecht and other Chabad rabbis in the area give. “For me, it is an important part of my life.” Vichinsky participated in an earlier learning initiative of Hecht’s—a 10-year weekly study of the entire Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, the popular abridgement of the “Code of Jewish Law” authored by 19th-century Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfried. Their efforts were celebrated in a communal siyyum (completion ceremony) in 2016.

A Daily Connection That Will Survive the Pandemic

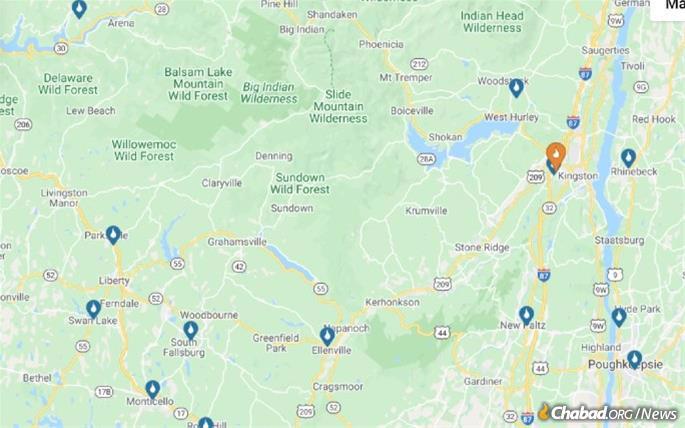

Hecht has built an extensive learning program that involves other area shluchim and has continued virtually during the coronavirus pandemic, including Rabbi Mendy Karczag of Chabad of Woodstock, Rabbi Moshe Plotkin of Chabad of New Paltz, Rabbi Avrohom Itkin of Chabad of Greene County and Rabbi Shlomie Deren of Chabad of Ellenville. “Daily Connection classes were at 9 a.m. and 9 p.m.—every 12 hours,” Hecht noted proudly. He invited the Woodstock rabbi to teach Tanya on Mondays, and the New Paltz rabbi to teach about holidays on Tuesdays. Hecht leads a “Shmooze with Friends” class on Wednesdays, and Rabbi Yaakov Raskin teaches parsha on Thursdays.

Hecht is proud of the learning program he has designed and built. “It is here to stay, no matter what, even after the pandemic.” And it reaches far beyond Kingston. Hecht references a member of the community who recently relocated to a small town in Mexico, noting that “she has her Yiddishkeit and community because of this.”

Vichinsky and Hecht speak with excitement about the mikvah, which will soon serve the community. Hecht has also helped expand the Chabad shluchim presence in Kingston and in Ulster County, noting that now “my sister and brother-in-law are here in Kingston. My brother and sister-in-law are 20 minutes away in Rhinebeck. And more young people are coming here.”

In addition, there has been a Chabad presence on the SUNY New Paltz campus—14 miles to the south—since the Plotkin family arrived 17 years ago. Vichinsky notes that “they do wonderful work with the college students. It gives them a religious alternative in a liberal college.”

Hecht has seen a shift in Kingston’s Jewish community over the years, “from mostly 50-year-oldplus adults who attended shul mostly on the High Holidays to younger singles and married couples in their upper 20s and 30s.”

He notes another important sign of growth—the fact that “we are slowly finding more kosher products in the stores.” Kingston isn’t far from major Jewish population centers with extensive selections of kosher food; both Monsey and Albany are an hour away.

The local Chabad shluchim have also found a creative solution for helping their children receive a Jewish education. “Four shluchim families drive their kids each day to Albany,” reports Hecht.

Families relocating from urban areas are already finding Kingston to be a desirable destination. Vichinsky has already noticed that “some families left the city during Covid and came to Kingston. It is touted as a place to be.”

Musician Ellie Macias had been planning to relocate from Brooklyn to Kingston even before the pandemic. In 2018, as their children got older and some were already out of the house, he and his wife purchased a house in Historic Hurley. They completed renovations just before March 2020. “Being in nature was very attractive.” Macias noticed a movement of others seeking an “alternative lifestyle and wanting to be in nature.”

Kingston’s cultural life also appealed to Macias. “There is a movement of musicians to the Hudson Valley. It has become a center for musicians.” Macias, originally from Gibraltar, studied Ladino Flamenco and jazz guitar at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. He now has a recording studio in his house.

Macias has noticed some young couples moving into town and feels there is “potential for more people to start to come.”

He acknowledges that the marketing of a shul can be a challenge. But he credits Hecht for his ongoing efforts to grow the community. “They are a great team, and they are amazing shluchim in terms of how much they give of themselves. They know everyone and genuinely enjoy chatting with everyone,” says Macias.

Macias is particularly pleased by the thriving congregation, as he has been saying kaddish daily this year in the synagogue thanks to the minyan there.

He also sees great potential in the future of Kingston as a whole: “It is a well-kept secret but once people know about this ideal lifestyle, they will come.”

Vichinsky feels the secret is already getting out. “Chabad in the Hudson Valley has grown exponentially over the last decade,” he says. As Hecht steps back and reflects on what the shluchim families have accomplished thus far in Ulster County, he reports: “This is what the Rebbe wanted from us—to see and feel a need, and to fill the needs of the community.”