Original Article is Published on JNS.org

Throughout Jewish history, public fasts have responded to and beseeched God for mercy at times of great pain and uncertainty.

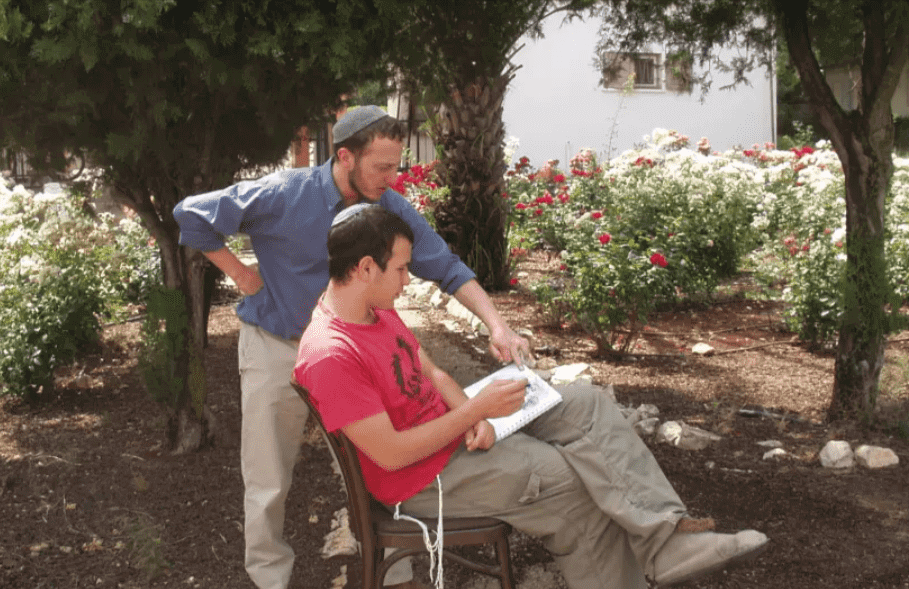

Rabbi Eric Woodward of New Haven, Conn., plans to join more than 675 rabbis, cantors and Jewish community members in the United States, Canada, Europe and Israel in a communal fast day on Oct. 12.

In an email on Wednesday, the rabbi of Beth El-Kesser Israel strongly encouraged the Conservative synagogue’s community to join him in abstaining from food and drink—something that Jewish communities have done throughout history in the face of tragedy, troubling uncertainty and other times that call for beseeching Divine mercy.

“With feelings of utter horror for the fate of the kidnapped, and with worry for the soldiers of the IDF, I am as mara d’atra declaring a taanit tzibbur, an obligatory communal fast, for our community tomorrow, Oct. 12, 27 Tishrei,” he wrote, using the English and Hebrew calendar dates. (Mara d’atra is Aramaic for a religious adjudicator who is considered to have authority in a certain place.)

The fast was called to begin at 5:38 a.m. at dawn and to end at 6:58 p.m. at nightfall, New Haven time.

Woodward told JNS that he and a rabbinic colleague had considered declaring a public fast when he received an email from the Hadar Institute—a Manhattan-based center of Jewish life, learning and practice—announcing a fast day.

“We stand in horror as Hamas has taken over 100 Israelis and other citizens hostage, among them infants, toddlers, entire families, the elderly and Holocaust survivors,” the Hadar email explained. “While political and military leaders are pursuing pathways to their release, we have a religious and communal obligation to stand up for the victims and to cry out to God.”

Woodward, who has great respect for Hadar and its rabbis, announced the fast in his community and signed on to a list of rabbis, cantors and communal leaders planning to do likewise. At press time, the list—which appears to span several religious denominations—numbered more than 675.

‘A gut punch’

“It feels like a very important Jewish moment. It is something we can do to unite our prayers with our bodies and our existence,” Woodward told JNS.

The rabbi has found himself feeling “unwell and physically nauseous” upon seeing new, horrifying images from Israel of the aftermath of Hamas attacks on Oct. 7 which Israeli President Isaac Herzog and others have called the bloodiest day in Jewish history since the Holocaust.

“It feels like a gut punch,” Woodward told JNS. “A fast feels like a Jewish way to deal with it.”

Woodward’s colleague Fred Hyman, the rabbi of the nearby Westville Synagogue, is encouraging his Modern Orthodox community to fast as well.

“At times of great distress, the community declares a public fast with prayers of supplication as a spiritual response of reflection and introspection,” Hyman told JNS.

The concept of a public fast in the face of danger or trauma comes from the Mishnah, in a tractate called Taanit (“fasts”), according to Woodward. In the Mishnah, which was codified in the third century, that danger includes droughts and persecution of Jews.

“This clearly fits,” Woodward told JNS of the present moment, despite the fact that rabbis don’t typically call for fasts in the month of Tishrei—that of the High Holiday season. (There are two set fasts in the month: Yom Kippur and the Fast of Gedaliah.)

“This is the right moment to call a fast,” he said.

Fighting back against danger

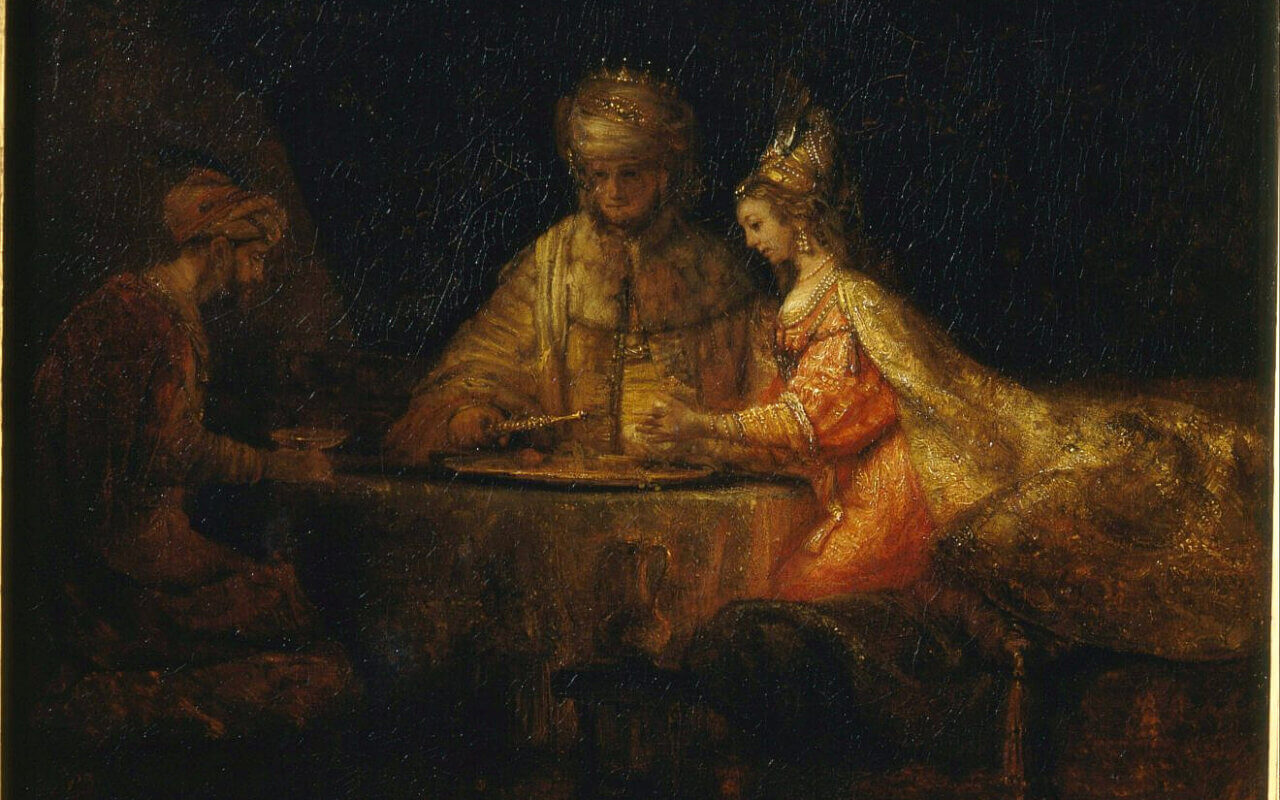

Laura Shaw Frank, of Riverdale, N.Y., told JNS that she finds the idea of a fast meaningful, having always connected personally with the biblical character of Esther—who fasted and called for the Jewish community to fast before she went to plead on their behalf to King Ahasuerus.

“I connect with Esther and the notion that Jewish people can be called to fight back against danger and oppression through a religious act,” said Shaw Frank, who directs the American Jewish Committee’s Department of Contemporary Jewish Life.

Linda Roth, of Woodbridge, Conn., also thinks of Esther and Mordechai when she thinks of participating in a public fast.

“We are in a critical time to put on sackcloth, sit on the ground and cry,” Roth told JNS.

Roth spent a lot of time in a bomb shelter in Israel in the summer of 2014 with her daughter, son-in-law and their newborn child. Roth told JNS that helping out by providing food, clothing and other supplies to those who need them in Israel is important. But it is “not sufficient.” Fasting will be a meaningful way to show concern, she thinks.

“I have never seen it in our lifetime,” she said. “This is a serious moment, and I am grateful they called one.”

‘I welcome the opportunity’

While rabbis declared the fast for Jews worldwide, at least one pro-Israel, Zionist non-Jew, who is a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon) also plans to fast on Oct. 12.

The Dallas native Joseph Kline, a former U.S. Army intelligence analyst currently in his second year at Harvard Law School, couldn’t stop thinking about the attacks in Israel and about his Jewish friends serving in the Israel Defense Forces, particularly after witnessing a pro-Hamas rally at Harvard University.

“I am very religious and am praying for the IDF soldiers on the front lines,” he told JNS. “I had mentioned the idea of fasting on behalf of Israel to my Jewish friend since we fast once a month. She said that there was going to be a fast.”

“I fasted alone on behalf of Israel on Sunday,” he said. “I welcome the opportunity to join my brothers and sisters around the world in fasting on Thursday.”