Original Article on The Jerusalem Post

The happy boys danced, sang, cheered for their teachers and even jumped on tables when the head of school called their classroom by name. While the enthusiastic pupils have been learning together daily for three months, they were only seeing their teachers and fellow students in person for the first time – the boys, ages six to 14, spend up to six and a half hours a day together, where they participate in Chabad Shluchim (emissaries) Online School.

The young yeshiva students who came to Brooklyn on November 23 – Thanksgiving Day in America – to participate in a “Day of Celebration” were from Mexico, Canada, Venezuela, England, Sweden, Norway, and places in the United States such as Tennessee, Rhode Island, Iowa and Alaska. The boys were accompanying their fathers attending the 5,000-person International Conference of Chabad-Lubavitch Emissaries.

Their parents direct Chabad Houses around the world, and agree that the Online School, pioneered by Chabad, has helped make it possible to live and serve in communities without any Jewish day school. The Online School has made it possible for their children to receive a “proper Chabad education” without being home-schooled. The spreading of Jewish knowledge and observance were important core principles of the late Lubavitcher rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh leader in the Chabad-Lubavitch Hassidic dynasty and one of the most important Jewish leaders of the 20th century.

The fathers and sons were visibly excited as they entered the nicely decorated ballroom at Congregation B’nai Jacob in Park Slope, Brooklyn. “I just saw my kid meet his classmates for the first time in his life – this is a very beautiful moment,” observes Rabbi Benny Hershkovich of Los Cabos, Mexico, here with his eightyear- old son Kovi, a third grader.

Rabbi Yossi Laufer of Warwick, Rhode Island, is pleased with both the learning and the camaraderie his 12-year-old son, Dov Beir – running around with his friends and teachers and enjoying the food and drinks – receives in the program.

Observing the room full of boys bantering and running, Hershkovich says: “I guess they are not really trained in the classroom to be quiet!” Malkie Gurkow, one of the program’s principals, a parent, and one of the few women on hand, notes, “You can feel the excitement. It is palpable. I have two boys in the school – they wait for this event all year!” According to Devora Leah Notik, associate director of the Nigri International Shluchim Online School, “a small group of parents approached the Shluchim Office about 10 years ago and said, ‘We don’t have the infrastructure where we live. And we want our kids to learn with others who understand the challenges of living far off, on shlihut.”

The Shluchim Office – the central addresses for anything an emissary might need – responded to the request which began as a telephone conference call before moving to Skype. “Then it grew and grew and grew…” reports Notik.

The Nigri International Shluchim Online School currently operates as four separate divisions, serving four geographic areas across the world: Western America, Eastern America, Euro/Asia (English Division) and Western Europe/Asia (Hebrew Division). Even though it’s online, the pupils are separated by gender. The academic year generally runs from early September through the end of June.

THE 380 pupils in the American division are supervised by two principals, Malkie Gurkow of Massachusetts and Rabbi Yaakov Ringo of Montreal. The program’s central offices are located in Brooklyn, which serves as the regional hub for the American divisions (359 children from 186 families), as well as for the English- speaking Euro/Asia division (37 children from 32 families).

An office in Israel provides administration, support and a teaching center for pupils attending the Hebrew division (279 children from 113 families), which caters to families currently living in Europe, Asia, Israel, Russia and Ukraine, where the children’s primary language is Hebrew.

The curriculum, teaching methods and special school-wide programming are unique to online learning.

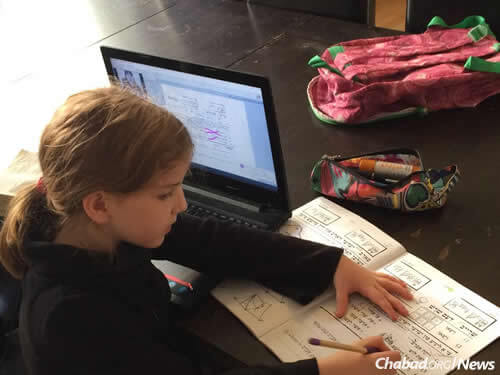

The regularly updated curriculum needs to be formatted for posting in both Power Point and slideshow mediums. Pupils wear uniforms (a vest with the Chabad Online School logo), have webcams and microphones, raise their hands to participate, and take online quizzes and tests. They view their teachers and fellow pupils on half of the screen, and view white boards and slides on the other half. Teachers sometimes utilize breakout rooms where children learn and work in pairs or larger group, and teachers freely move between rooms.

Chabad families often have numerous children learning at the same time.

“In some families, the children are all lined up at a table in one room,” notes Notik. “In other families, they are spread out all over the house. It is fun to see.”

Four-year-olds sing, and learn about the weekly Torah portion and mitzvot for 60 to 90 minutes, while eighth-grade boys in the transition to yeshiva program learn for six and a half hours a day. Most of the boys will begin boarding at yeshivot in Israel or America at age 14. Teachers across the different age groups work to synchronize breaks – every 45 minutes – and lunchtimes to make it easier for families.

At the Chabad House in Copenhagen, two of the Lowenstein girls spend a lot of time at computers in different rooms of their fifth-floor apartment. “It functions as any ordinary school, only online,” observes Rochel Lowenthal, mother of nine. “Classes, extracurricular, school projects, color war, monthly themes, contests, production, PTA, etc. We have kids in the European division and two in the American division – which means we are on from 9 a.m. until 6 p.m.”

Lowenthal, who was not in Brooklyn at the Thanksgiving conference, is pleased and relieved with all the Online School offers.

“We were, thank God, able to keep our older kids home till high school thanks to SOS [Shluchim Online School]. Four of our kids have graduated” – the graduation ceremony is online – “and have, thank God, fit right into high school.”

Her other children in school – 12-year-old Chana in seventh grade, nine-year-old Devorah Leah in fifth grade, and seven-year-old Sheina in second grade – got to finally see their fellow pupils face to face at the conference.

“There is always an SOS day of celebration, where the kids meet their classmates and teachers. It’s very special.”

Parents have a mostly typical school experience.

They attend online parent conferences, pay tuition (scholarships are available), and purchase uniforms and books, though children in faraway places sometimes receive materials in PDF format to cut down on wait time for shipping. The curriculum focuses on religious subjects of all kinds: prayer, Hassidic philosophy, Torah and Talmud, and others.

Children living in so many geographical regions do pose logistical issues.

“Australia and China are challenging – there is a 13- hour time difference!” says Notik, who hopes to one day open an Asia division. “In addition, we have to deal with changing clocks at various times in different places, we have to provide extra time to translate for non-native English speakers, and we don’t give homework during Hanukka since it is a busy time at Chabad Houses.”

However, not everything is rosy: Rabbi Zalman Lewis of Brighton, England, notes some additional challenges of online learning. “My wife never breathes!” he says. “With a normal school, kids leave in the morning, come home at a normal time, and there is time to clean the house. Here, the kids are always home.”

The computer itself can be a source of distraction.

Lewis points out the need to constantly monitor the children. “We parents play a huge role here – one son is a tech geek, so we face his computer to the door and monitor him on the computer.”

“We need to engage the students continuously,” adds Rabbi Shmuel Jacobson of Crown Heights, New York. “We have to be more entertaining than the computer.”

The program offers 24-hour tech support and constant attention to online security – with separate teams based in the US and Israel.

Pupils with diverse learning needs are also able to participate. “That was the rebbe’s mission – to provide a superior, well-rounded Jewish education for every child and to answer the needs of every child,” says Notik. “We are able to include students by offering shadows, homework helpers, tutoring services, paras and IEPs (individualized education plans). We cater to multiple learning styles and have lots of visuals.”

WHILE MANY ultra-Orthodox groups have historically held negative views regarding the use of Internet and technology, Chabad has a long history of embracing that technology. “The rebbe spoke about this early on – radio, TV, all of God’s creations are tools and the medium to spread good and knowledge,” Notik explains. “The rebbe appeared on the radio, and the farbrengens [hassidic gatherings] were on TV. And Hanukka parades and rallies were broadcast by satellite – people felt such Jewish pride. Even if they weren’t in the actual place, it was accessible. Now, we have the Internet, which has unlimited reach. This is an incomparable tool…”

Simon Jacobson, author, publisher of the Algemeiner Journal (a New York-based newspaper covering Jewish and Israel news) and a Lubavitcher hassid, adds, “The current technological revolution is in fact the hand of God at work – it is meant to help us make God a reality in our lives.”

As the Jewish educational world continues to seek ways to meaningfully incorporate computer technology and online learning into Jewish educational programs, Esther Feldman, director of Information Technology and Financial Services at the Lookstein Center for Jewish Education at Bar-Ilan University, offers a keen observation and take-home message from the Chabad Online School. “It is the experience of learning that counts. Good online learning has to be about the experience – not just about the content.”

It is unlikely that any online learning program can match the experience and enthusiasm of the Shluchim Online School. The Day of Celebration ended with the International Roll Call. As director, Rabbi Yaakov Ringo called the name of each class, B2 through B7, and the boys erupted in cheers, shook glow sticks, and danced around the room.

In case you’re wondering where all the girls are, they are at home running the Chabad House while the dads are here running around with the boys, as boys and girls study separately. But in just a few months they will switch roles during the women’s conference.