Original Article in The Times Of Israel:

NEW YORK – By age four, Jason Fuchs was a TV addict. But unlike most kids, he didn’t want to just sit in front of the boob tube, he wanted to be on it.

“My parents would call out to me while I was watching, and I didn’t respond to anything. I remember pointing to the TV and saying, “I want to be in the box–the thing I was staring at,” Fuchs told The Times of Israel last week.

Back then he was too shy to talk with his father’s agent friend; he’d been taught not to speak with strangers. But a follow-up meeting three years later put Fuchs ‘in the box’ – and on the big screen.

Over the past 20 years, the former child actor has appeared in plays (“Abe Lincoln in Illinois”; “A Christmas Carol”), TV shows (“Law and Order: Criminal Intent”; “Law and Order: Special Victims Unit”; “All My Children”; “The Sopranos”) and movies (“Flipper”; “The Hebrew Hammer”; “Mafia!”). The Columbia University graduate has also written scripts, including “Ice Age 4” and “Rags.”

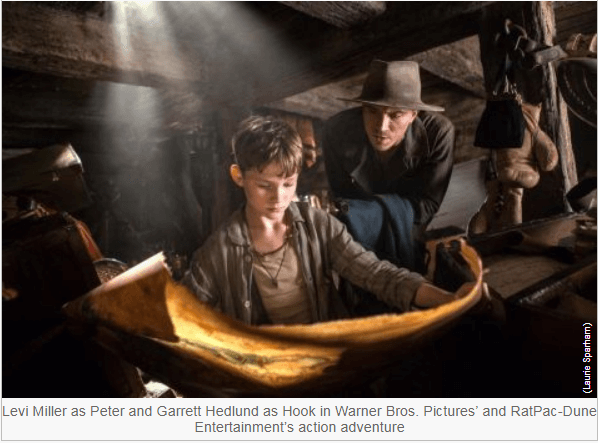

And it his screenwriter chops that has Fuchs, now 29, poised to become a hero for other little television-obsessed boys, with the October 8 debut of his family blockbuster, “Pan.”

Growing up, what were some of your childhood interests outside of TV, movies and acting?

My parents insisted I attend a regular school [as opposed to a performing arts school] until high school. And I never got too successful! It is harder when you are Macaulay Culkin – always working on a regular basis.

My two great loves are basketball and foreign affairs. I have always been a diehard New York Knicks basketball fan. I remember watching the Gulf War on CNN. I knew who Dick Cheney was even when I was a little kid and I had a Gulf War trading card collection.

When 9/11 took place, my father worked across the street from the Twin Towers. He saw them fall and came to get me at school that day, covered in soot. I sort of dove in to learn about the Middle East after 9/11. I wanted to understand everything.

Has this interest in the Middle East continued?

When I was 17 years old, I had an internship at GIS-Global Information System, an independent government intelligence service which gives second opinions to governments. During freshman year of college, I was their UN correspondent.

GIS is run by a brilliant Australian Gregory Copley and Israeli Yossef Bodansky, author of “Bin Laden, The Man Who Declared War on America,” which is ironically the first book I read after 9/11. Bodansky is a rock star to me – he is brilliant and kind. I still have an obsession with current affairs and the Middle East and keep up as closely as I did when I worked there.

Did this interest in Middle East Studies continue at Columbia University?

I took some Middle East courses. I studied with Rashid Khalidi [the Edward Said Professor of Arab Studies at Columbia University]. He is a nice guy, but he didn’t like me. We did not share all the same perspectives. It is not so much a Professor Khalidi issue as a Columbia issue – there is some intolerance for a diversity of opinions and they don’t foster an atmosphere of healthy dissent.

What does Israel mean to you?

I have never been to Israel. It is very important to me, I feel a very strong connection and affinity, and I NEED very much to go at some point – sooner than later. I went to Hebrew school, and had a strong sense of yiddishkeit and appreciation for Jewish history.

I am the grandson of two Holocaust survivors (my grandfather is still alive). I am also cognizant of the threats the Jews have faced historically and am aware of how significant it is to have a national homeland like Israel whose founding ethos is “Never Again.”

So knowing that your grandparents were in the Holocaust and didn’t have an Israel to run to, it is a very powerful thing to know that such a place exists.

I also feel a strong connection with it as a lover of democracy. I like living in a democracy, I vote, I do jury duty, I think it is a good way to govern. Jewishness aside, I also feel a kinship to Israel in the same way I feel a kinship to democracies all around the world.

You sound pretty ‘connected’ Jewishly. Do you have a favorite holiday or story?

The holiday that on an emotional level I registered with has always been Passover. For me, the story of Passover is the best story in the Old Testament. It is kind of the template for every movie that I enjoy. The savior motif, the idea that there is someone destined for something special, to lead his people – that is Moses, that is the Exodus story.

You see echoes of that in Luke Skywalker, Harry Potter and in this version of the Peter Pan story. Peter is, in this telling of the story, the Chosen One. He is a messiah-like figure who is fated to do something extraordinary. He rises up from essentially, bondage – he is an orphan in a horrible orphanage – he nuns mistreat him and the other boys – and he rises up to be The Pan, the savior of Neverland.

And that’s not an original idea at all. It is a very traditional idea, one that resonates for me in some of the stories that mean the most to me, and hopefully resonates for so many people.

How did the Pan story make it to to the big screen?

When I was 9 years old, I got stuck on a Peter Pan ride with my dad, and was stuck for 20 minutes in a pirate ship. I was always a curious kid with an insane number of questions for my dad: Why is Peter Pan, Peter Pan? Why can he fly? Why do he and Hook hate each other so much? What is Neverland? Why is he there?

By the way, that’s not an un-Talmudic way to approach things for a nine year old.

What kept me motivated is when no one bought the script. I didn’t write it on spec. I was too passionate. I thought I’d pitch it and maybe someone would bite but no one did. Finally, I met with Warner Brother’s exec Sarah Schechter and she told me to do it. It is a fairy tale story within itself!

What was it like working with Hugh Jackman?

Hugh Jackman is amazing. With a movie star of that kind of measure, you don’t know what to expect. Hugh is the most normal, kind, decent human being you’d ever hope to work with. When your most famous actor is as big of a mensch as Hugh Jackman is, everyone has to be a mensch. It sets the tone for the entire crew.

What does it mean to you personally to have Pan coming out in Israel?

I love the fact it is opening in Israel. It is very meaningful that something that meant so much to me, the story I told my agent, my parents and my girlfriend – is out there for people in Israel who have no clue who I am to go and see.

You’re rumored to be writing the “Wonder Woman” script starring Gal Gadot.

Anything related to DC Comics is like working with the CIA – there is a code of silence. I have read what you have online about what my involvement with that project might be. I can only speak as a fan – I always loved comics as a kid. I am as hardcore a DC Comic fan as there is. But in terms of my involvement, I cannot comment. I think Warner Brothers has set the film “Wonder Woman” to come out in June 2017.

What do you have in the pipeline? What are you currently working on?

I recently wrote a movie script for “Break My Heart One Thousand Times,” a supernatural thriller where ghosts are part of everyday life and a TV pilot for TNT, “Black Box,” a conspiracy thrillerish TV show.