The Original Article is Published at The Jerusalem Post

Parting wisdom for potential olim: Surround yourself with a familiar environment, even in a foreign country.

When the Sone family made aliyah from Montreal, Shawna promised her children they could continue attending Camp Ramah, their beloved Jewish summer camp in Canada.

However, in Israel she was surprised to learn that for many of their children’s friends, summers did not have a similar experience and that families barely survived the often dreaded hofesh hagadol, the long, unstructured summer break.

The chef, cookbook writer, mother of three sons, and board chairperson of the Morris and Rosalind Goodman Family Foundation was inspired to share the magic of sleepaway camp with large numbers of Israelis, so she founded Summer Camps Israel to provide camp opportunities to Israeli children over the summers. Now she offers these camp experiences to Israeli children impacted by the current war.

While the upbeat, always positive Shawna always loved Israel, she was in many ways an unintentional olah.

She grew up in Montreal in a family that “stacked the deck,” she says, in favor of the children falling in love with Israel. They attended Jewish schools and camps, participated in the community, visited Israel regularly, and had tremendous pride in being Jewish.

Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper speaking at 2009 Canada Day celebrations on Parliament Hill. (credit: KASHMERA/CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)/VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

“My father woke up and went to bed with the news of Israel, but we were Diaspora Jews,” she notes, “Israel was ‘over there’ and no one ever encouraged me to move – not rabbis, not school, not camps.” She enjoyed her junior year of college in Israel, but aliyah was not in the plans.

In contrast, her husband, Todd Sone, grew up in a very Zionist family in Toronto and always had aliyah on his mind.

When Todd was in ninth grade, his pharmacist father spent a sabbatical in Jerusalem with the family, and Todd enjoyed an incredible year in French Hill, attending the Himmelfarb School. His friends left glowing comments in his yearbook, complimenting him for fitting in so nicely and for being such an important part of the class.

Todd dreamed of returning to Israel and finally did for his junior year of college at Hebrew University. Shawna playfully notes that Todd “had aliyah in his blood.” There is some friendly disagreement about whether his desire to make aliyah was disclosed on their first date. “He claims he told me he planned to move to Israel. I think I wasn’t listening.”

The two married in 1996. At around the 10-year mark, the idea of aliyah started nagging at Todd. The family began spending a month every July in Israel, where the kids attended Ramah’s Jerusalem Day Camp. They then returned to Ramah Canada for the second month.

The couple began to realize just how good their kids had it in Montreal. Family, community, and friends “ticked every box.” They began thinking about ways to get their children out of their comfort zone – something “adventurous” to “build resilience,” Shawna says. She considered “random countries, like Belize,” but settled on relocating for a year to Israel.

They set out for their furnished Ra’anana rental apartment with “14 hockey bags” and “pretended to live here.” Todd continued working with his North American-based employer.

Meeting Canada’s prime minister and then making aliyah

In January of their Israel year, then-prime minister of Canada Stephen Harper came to Israel for a visit.

“My mother of blessed memory was a huge fan of his,” Shawna says. “She used to say we will never live through a time when we will have a prime minister who is so pro-Israel.” Shawna was excited that her parents would be in Israel, as they were invited to be part of the trip and the opening of KKL-JNF’s Stephen J. Harper Hula Valley Bird Sanctuary Visitor and Education Centre.

Sadly, her mother, Rosalind, was diagnosed with lung cancer and was unable to make the trip.

Shawna and Todd were offered the chance to join the prime minister’s delegation. “The country was lined with Canadian flags. I realized you don’t have to hate something to love something. I can be a bissel [a bit] of both. My identities could be aligned with one another.” She smiles, recalling, “Bibi was singing ‘Let It Be’ with Harper at the David Citadel on karaoke night! Why are we leaving so fast!?”

THE SONES decided to stay, moving back to Israel “for good” the following year.

At the time, their boys were in grades 4, 7, and 11.

“There is never a perfect age,” Shawna admits, crediting her community for what soon became a successful aliyah experience. Friends “took our phones and put in their numbers.” At first, she found this a little aggressive but soon came to appreciate these were the important go-to people to find out “what time school ends, how to fix a flat tire, where to find a guy to do this and that. Those numbers were lifelines!”

She credits her friends and community for helping: “Everyone was once where you are, and they want you to succeed.” She considers this a “unique experience” in Israel, where “everyone pays it forward, is authentic, genuine, and kind. There is an attentiveness to others here.”

Shawna also credits Todd for being “the driver.”

“Todd had this insatiable itch to be part of the story. He didn’t want to ask ‘Where was I?’ when we had this opportunity.” She adds, “You need a driver. I was willing to go for the journey – and were both on the same page at the end of the day.”

She acknowledges that you “have to come with 500% of will” – everything can knock you down. Fluency in Hebrew, she says, is crucial – even in a community with many Anglos. “Language is the most important thing – and Todd had it. I am still in ulpan – and will be until the end of days!”

Even without the language, Shawna has found her purpose in philanthropic work, with its base in summer camps. She met Todd at Ramah, and her deepest friendships came from her camp experience. “I am beholden to camp,” she says.

“I started asking questions about what kids do here in the summer. Why are the lights off in June? Why was summer break dreaded by all?” She knew she wanted to help grow sleepaway summer camp in Israel.

In 2019, she started the Forum for Summer Camps to bring informal education professionals together under an umbrella. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, two 10-day camp programs – one of which was My Piece of the Puzzle, a program that integrates children and youth at risk and those with disabilities – opened in 2020. They continue to grow. There are currently 28 camps. They served 15,000 campers last summer.

“We are trying to be reflective of the diversity of Israel,” notes Shawna proudly as she describes one camp serving Jewish and Bedouin girls. “We hope that camp will become part of the journey of becoming an adult in Israel. We hope that every Israeli who wants it will have a 10-day camp experience and feel it for life.”

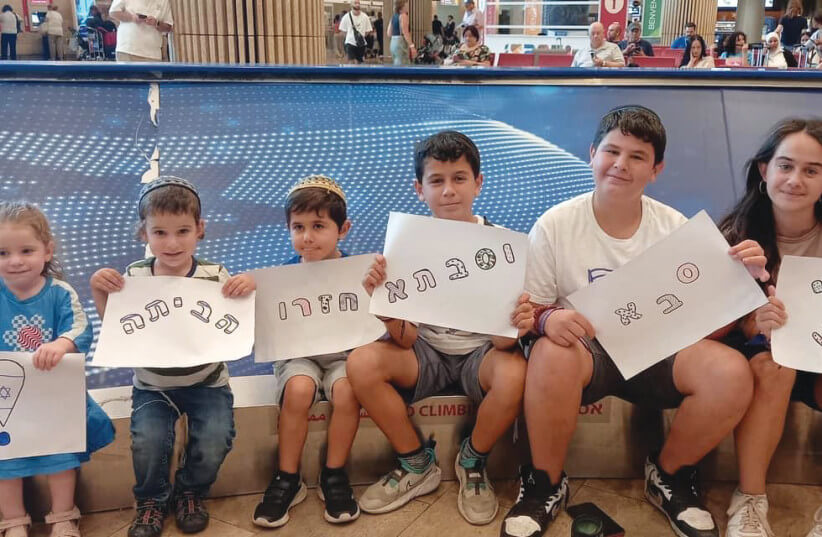

The current situation in Israel has led Shawna and her team to offer Winter Boost Camps, three-day camp experiences for children who have been evacuated from their homes. To date, they have served 600 children.

While Shawna’s camp work continues to fill her time and renders great satisfaction, the professionally trained chef finds ways to combine all of her interests.

She has led Shefa, a women’s trip to Israel “to celebrate Israel’s abundance” and to be inspired by Israeli women making an impact.

Shawna, who also teaches cooking classes, reports, “I use food mixed with philanthropy.” For example, she teaches a class at Leket, Israel’s National Food Bank, on how to cook with leftover food, and to raise awareness about the organization’s mission.

She offers parting wisdom for potential olim: Surround yourself with a familiar environment, even in a foreign country. She notes that there is something for everyone in her Ra’anana community, such as English-speaking mahjong groups, yoga classes, and Torah study.

She sums it up: “Find your comforts!” ■

SHAWNA GOODMAN SONE, 52 FROM MONTREAL TO RA’ANANA, 2015