Original Article Published On The Jerusalem Post

Nearly 30 participants in a recent Taglit-Birthright Israel trip for people with Autism Spectrum Disorder received insight into what Israel can offer to employees on the autism spectrum.

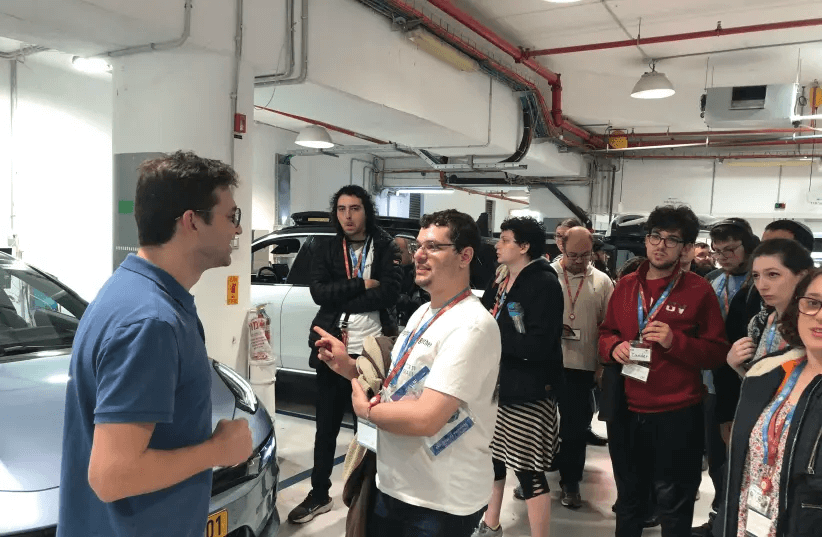

One of their stops was at Mobileye, the Jerusalem-based company that develops autonomous driving technologies and advanced driver-assistance systems.

Thanks to a meaningful partnership between the Jerusalem-based Shekel: Inclusion for People with Disabilities, Mobileye and the hard work and support of Shekel-turned-Mobileye employee and team lead, Mollie Goldstein, 13 people on the autism spectrum work in data annotation at the hi-tech company. The autistic employees review, tag and label video clips of traffic signs, animals and other things on the road which drivers might encounter.

“I was impressed with Mobileye for a variety of reasons,” said Jared Ramis, a 30-year-old Taglit participant from Chicago notes. “For starters, I’m fascinated with companies that develop technologies and systems that help keep drivers safe. We can never have enough of those. But, I also respect their hiring process. I am a firm believer in equal opportunities for employment and it filled me with joy to see them hire people on the (autism) spectrum. I firmly believe that people on the spectrum are as capable of being great employees as anyone else and I feel that the people they hired are a great asset to their company.”

The 20 Birthright participants from across North America enjoyed their small group meetings with workers who, like themselves, are on the autism spectrum. They also had a great time touring the garage filled with cars and learning about how Mobileye’s technology works.

Success through Mobileye

Eli Schreiber, 29, has been working at Mobileye for six years. “I live in an apartment run by Shekel and heard about the program at Mobileye through my roommate, who worked at Mobileye. When I heard they had this program, I literally begged for a job,” reports the Jerusalem resident who made aliyah from Teaneck, New Jersey, in 2002. “I wanted a job where I could be on a computer all day. I applied and got the job.” At the time, the program was housed in Shekel’s building in Jerusalem.

Shekel offers a wide range of services for people with disabilities, including vocational rehabilitation, therapeutic services, community living, enrichment and leisure. Shekel participants are trained and employed in various jobs around Jerusalem, the Knesset, candle making, toy assembly, graphic design and retail at Ha Metzion vintage and secondhand stores.

Mollie Goldstein recounted that Shekel’s partnership with Mobileye started small and gradual when Mobileye was a startup. “It began with an initial conversation and a connection and resulted in a small-scale project with four or five Shekel participants with computer skills working at Shekel’s campus on a computer project set up by Mobileye. Over time, as Mobileye grew, six to eight Shekel participants were on board, working at Shekel.” In 2018, as Mobileye grew and acquired new office space, the Shekel workers relocated to the Mobileye campus.

Schreiber enthusiastically described his work and experience at Mobileye. “I have always worked in data annotation – I look at images and videos and look for images like a speed limit sign and tag it. We input the info into an algorithm and it does its machine learning.” Schreiber’s work has evolved over time. “Now, it is a little different. We tag animals and do something for facial recognition. We look at the faces of people driving cars and make sure they are paying attention to the road.”

SCHREIBER ENJOYS his work and his role on the Mobileye team. “I love the fact I am helping to build a machine that will be able to drive us without us having to touch the wheel. I’d love to stay forever,” though he expresses some concerns about his future. “My job will probably become obsolete. As machine learning gets better, they will have to cut down on the number of teams.” Schreiber currently works five days a week for six and a half hours a day.

Schreiber likes coming to work each day and appreciates the work culture and attitudes he has experienced at Mobileye. “I love the fact that I can go in to work with a shirt that says Marvel (Comics) or (the heavy metal band) Slipnot. It is a very live-and-let-live culture. Everyone just does their job.” He acknowledges that he and his fellow workers on the autism spectrum are not a homogenous group. “Some people are friendly with everybody. Some don’t make eye contact, though this doesn’t mean they are not listening. I can talk to those around me but I am not so comfortable talking to those outside of the group. I have social anxiety to the extreme.”

In addition to learning job skills, employees develop social and interpersonal skills needed to succeed in the workplace. For example, they learn to arrive on time and to notify their managers of any absences in advance. They also have many opportunities to socialize in a welcoming, supportive environment.

Goldstein, 31, the Mobileye team leader, made aliyah 10 years ago, served in the army, worked in event planning and has experience working in the mental health field. She started working at Shekel in November 2020 and admits, “I hit the ground running.”

Goldstein does a lot behind the scenes to support her workers and to assure that the workplace is functioning smoothly. She writes articles about her program on the company’s internal website, runs events like panel discussions within the department so people see who they are and she makes sure her employees are held accountable for their work. “I pushed for the team to be considered like everyone else and helped managers do annual evaluations, which were both sensitive and effective.”

Goldstein’s love and care for her employees and for creating an inclusive workplace are evident. There are also challengers. She adds, “I believe in inclusion in the workplace. I want people to know who we are but I don’t want this to be a big PR stunt.”

For the visiting Birthright group, Goldstein’s autistic employees are a true success story and a source of inspiration and hope. In their lives at home, they face a daunting employment market for people with autism and other disabilities. In 2021, the unemployment rate for people with autism, even those with a college education, was approximately 85%. The current unemployment rate in the United States is 3.5%.

Lihi Lapid, the president of Shekel, praised the partnership with Mobileye.

“For Shekel, integrating people on the autism spectrum into employment that is both meaningful and appropriate to their ability and skills has always been a priority. Partnering with Mobileye, Shekel developed a unique training and support model that has been groundbreaking, allowing a group of 13 people with ASD to successfully integrate into Israel’s private sector hi-tech community for the first time. This is unprecedented in Israel, as is Mobileye’s wonderful partnership and enthusiasm for including people with ASD in the company,” she said.

LAPID AND her husband, former prime minister and current Opposition leader Yair Lapid, have an adult daughter with autism.

“As a mother of a young woman with autism, I know just how important work and other forms of being occupied daily are for young people with special needs. Like every adult, they also have a need and desire to do things that fulfill and interest them,” said Lapid.

Samuel J. Levine, professor of Law and director of the Jewish Law Institute at Touro Law Center in New York has also been similarly impressed with the project. He first made contact with Goldstein through a webinar he organized at Touro on the topic of autism and employment, before meeting her in person on a trip to Israel.

“I was particularly impressed with their approach toward autism employment, which is premised on finding a match between the skills of employees and the needs of the employer,” he said.

“It was clear to me that Mollie and the autistic employees have a mutual respect for each other and that others at Mobileye value the contributions of the participants in the program and view them as an integral part of the company. I was so impressed with this model and the attitude it represents that I organized another Touro webinar exploring the autism employment program at Mobileye, featuring presentations by Mollie and one of the participants in the program. The webinar attracted audiences around the world and drew very positive feedback, expressing the hope that the model implemented at Mobileye can be replicated in other autism employment programs.”

Inclusion, when done right, is financially beneficial for the company by identifying and matching company needs to employee abilities, explained Goldstein.

“A much wider range of tasks can be accomplished when employees bring different strengths and abilities. Examples of successful people with disabilities just go to show the brilliant minds we may miss if we overlook this segment of the population,” she said.

Goldstein added that there’s an additional benefit for Mobileye’s neurotypical employees. “They see the hurdles people have overcome to be given equal opportunities and see how important their job is to them.”

She pointed out that the participation of employees with disabilities in the workplace can raise morale and motivation for everyone.