Original Article On The Jerusalem Post

The effectiveness of MLB policy cutting down on lengths of games got me thinking that, just maybe, there is hope for cutting down on long synagogue services.

I turned on the radio a few nights before Shavuot, just as the New York Mets had won a nine-inning game. The announcer was praising the speed of the game – a quick two hours and 19 minutes. While this may seem relatively fast for a baseball game, it is not completely surprising or random. The trend toward faster-moving games is thanks, in large part, to a few changes implemented this season by Major League Baseball. The implementation of the pitch clock is an acknowledgment that three hours is just too long to sit for a baseball game.

Baseball games have averaged 3 hours or longer in every season since 2010. In 2021, games tended to last 3:11. The new rules have definitely helped shorten games. As of 447 games this season, the average length of a nine-inning game dropped to 2:38 per nine innings as compared to 3:03 last season. The 2:38 time is the lowest since 1984 when average games lasted 2:35.

Even 2:35 is long compared to the early 1900s when games finished in under two hours. The first time the average length of a game went beyond the two-hour mark was in 1934!

The effectiveness of MLB policy cutting down on lengths of games got me thinking that, just maybe, there is hope for cutting down on long synagogue services. Perhaps synagogues of all denominations can take a lesson from Major League Baseball. In an age of shortened attention spans, people simply don’t have the patience for regular Shabbat morning prayer services which go past the 2-hour mark.

For a while, synagogues were on a good track to keeping it short, mostly out of necessity due to the pandemic. Following a very long hiatus where there were no in-person prayer services, many synagogues resumed prayer services with extreme caution and modifications – outside or in a tent, socially distanced and with masks. And, there was a real effort to move things along quickly.

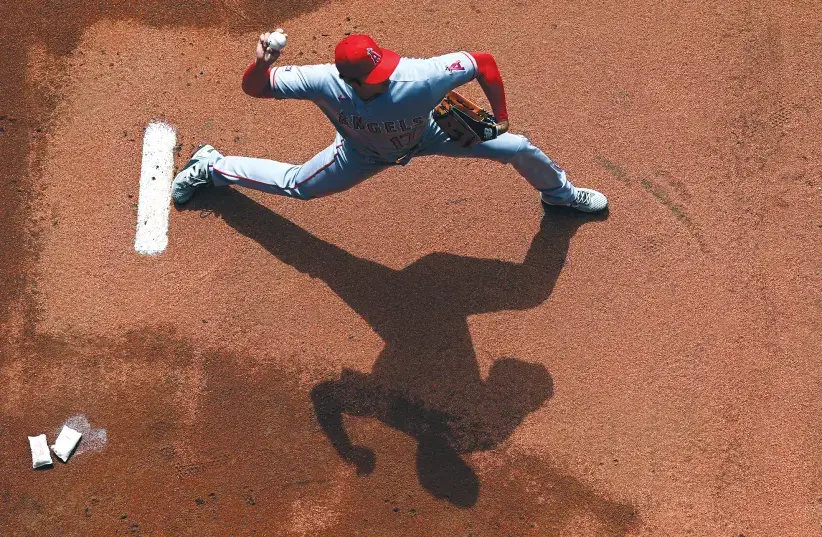

Jewish pitcher Eric Reyzelman has his sights set on a career in Major League Baseball. (credit: COURTESY/JTA)

How was this done? By eliminating non-essential parts of the service. People were asked to say the preliminary service at home and arrive in time for the “meat” of the Shabbat morning service. We were in and out – Shabbat morning took, well, just part of the morning and none of the afternoon.

ONCE SERVICES resumed back indoors, we continued to take precautions to move the service along. Who wanted to be indoors in close proximity to people for so long? One person handled all aspects of the Torah service from ark opening to lifting of the Torah. Torah honors were taken from one’s seat, therefore eliminating wait time for people coming up to the Bimah. In some synagogues, one person had all the honors! And Mi Sheberach, the prayer for the sick was eliminated.

Even on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur rabbis found halachicly acceptable ways to eliminate non-essential liturgical prayers. They also cut down on explanations, sermon length and extra honors like the numerous ark openings traditionally done before many prayers.

When the pandemic ended, there was speculation and hope that, perhaps we learned our lesson –that shorter is better. After all, who wants to spend all Saturday morning or holiday day indoors praying? Perhaps longer services were a thing of the past. In the post-pandemic area, might it be possible to both pray and take a walk with your spouse or play in the playground with the kids?

Sadly, we have slipped and returned to our old ways. One rabbi friend shared a recent conversation from Ravnet, the listserve for the Conservative Movement, about whether post-pandemic services should be kept at their new shorter lengths or fully restored to pre-COVID lengths. One rabbi – perhaps delusional – suggested, “We have so much to offer our congregants—why not make it [even] longer [than pre-pandemic]?!”

Is he serious?! It is time for synagogues to once and for all take a lesson from Major League baseball. What is the secret sauce? New rules and enforcement.

First and foremost, MLB has implemented the pitch timer. There is a 30-second timer between batters and then a shorter time limit between pitches. Once pitchers receive the ball, they must begin their motion within 15 seconds. If there is a runner on base, they have 20 seconds. If he goes over, he is charged with an automatic ball.

Batters also take responsibility for keeping games shorter. They must be in the batter’s box and be ready to go by the 8-second mark on the clock, or he is charged with an automatic strike. Batters get one timeout per plate appearance.

Even managers must take some responsibility for keeping things moving along. Managers, who are allowed to request a replay review, must do so more quickly than in the past. They have to hold up their hands immediately after the play in question to signal to the umpires that they are considering a challenge. In past years, they were given 10 seconds to initiate the review.

Once the manager alerts the umpire to a potential challenge, the umpire initiates a 15-second timer. The manager must then decide whether to challenge the call on the field before that timer reaches zero. Otherwise, any challenge request would be denied. Previously, managers had 20 seconds to decide whether to challenge.

COULD A shul timer reduce the length of prayer services?

When I shared my proposal with Theo, a baseball-loving bar mitzvah student of mine in New York City, he wisely asked, “Would there be a clock in shuls?” and “What would be the penalty for rabbis who go over?”

I thought about how this might be implemented in synagogues. Installing two clocks – one at the back of the shul for rabbis and cantors to see and one near the ark for the congregation to see are easy fixes. Perhaps the gabbai (warden) or a newly created position could be in charge of clock monitoring.

Penalties are easy to implement and enforce in baseball. What would that look like in synagogues? Perhaps a newly appointed shul “clock committee” chair can issue rabbis with a warning for a first offense. It could take the form of a yellow or red card in soccer and result in a “talking to” by the synagogue president.

Maybe he or she would be “blocked” from joining the congregational Kiddush for a second offense. The third offense for going over the two-hour mark might result in being “benched” for a Shabbat, “fined” (forced to work without pay for a Shabbat) and the filing of complaints with rabbinic governing bodies such as the CCAR (Central Conference of American Rabbis), RA (Rabbinical Assembly) or the RCA (The Rabbinical Council of America). Cantorial bodies would also be contacted as both clergy members assume responsibility for watching the clock.

Perhaps using a clock in synagogue seems punitive and just maybe some people actually enjoy sitting in pews for over two hours. As it turns out, we Jews are always watching the clock. Each Friday and Saturday, Shabbat start and end times are determined by clock times. And for those who enjoy sitting for longer services – enjoy.

We just ask that shuls post “run times” on their websites – just like movie theaters – so we can all make informed decisions about what to expect. There are hundreds of synagogues in Israel and dozens in America which are in and out in 90 minutes. It can be done!